Why Humans Forget: The Biochemical Legacy of Homo sapiens and the Overload of Modern Intelligence

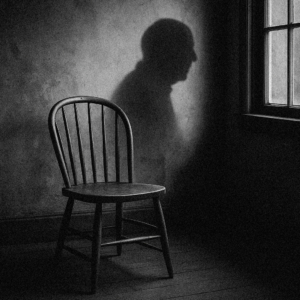

I remember the first time my mother looked at me and placed me somewhere else in time. In her mind I was still young. Not a child exactly, but not the man sitting in front of her. She did not lose my name that day. She lost the date of me. She shifted me backward along the curve of her life and anchored me in a room that only she could see. She could still tell stories from long ago with the detail of a careful archivist. She remembered a laugh in a kitchen full of steam, the shade of a coat she wore to a winter market, the smell of newspapers that stained her fingertips. But the present slipped. It would not hold.

As a scientist, I am trained to notice structure, to hear patterns others call noise. I read bones for a living. I read the tiny hints inside a wrist that tell me how a person worked, walked, carried, and aged. I track what time writes into calcium. I map how stress etches a rib. I put fragments together and let the body speak in a language that has no need for sound. That habit does not stop when I leave the lab. It sits with me at dinner, walks with me through a corridor, and stares back at me in mirrors.

So when my mother began to drift, I did not accept it as a vague event called aging. I treated it like a case. I followed clues. I reconstructed the scene. I asked what kind of brain would hold the past with such fidelity and refuse the present. I learned again what I already knew in another context. Memory is not one thing. Memory is a geography. There are older roads and newer roads. In Alzheimer’s disease, the newer roads crack first, often in the hippocampus and related cortical zones, while older roads remain passable for a time, carried by networks that have been reinforced by decades of repetition and meaning, including nodes within the medial temporal lobe and broad default mode circuitry that binds autobiographical time to identity (Jack et al., 2018; Small et al., 2011).

The pattern hurt to watch because it made sense. The modern world is fragile. It has not been rehearsed enough. It has not been folded into the deep grammar of the self. Newer memory depends on structures that are exquisitely sensitive to inflammation, cortisol, poor sleep, and metabolic insult. The hippocampus loves novelty and suffers for it. Under chronic stress, it loses volume and synaptic density. In plain words, it loses its ability to write new pages even while it keeps old chapters tucked away in safer places. That is not poetry. That is the neuroendocrine reality of a brain that never rests and a body that lives in a storm of signals that never end (Lupien et al., 2009; McEwen, 2017).

I began to trace not only what happens inside the brain but also what happens around it. I looked at water, light, micronutrients, movement, social rhythms, and information. I looked at what our species had for the last twenty thousand years and what we have now. I looked at what we removed for the sake of safety and convenience and what that removal cost. Homo sapiens did not evolve in sterilized rooms, under artificial light, with phones that wake the limbic system every ten minutes. This species grew under the sun, in the presence of real darkness, with mineral rich water, with food that carried signals the nervous system understood, and with silence that allowed networks to consolidate, prune, and strengthen. Our biology is tuned to that score. When we change the music, the dance begins to fail. Alzheimer’s disease has many stories that try to explain it. There is the story of amyloid, a protein that aggregates and settles like silt in rivers of cortex. There is the story of tau, a protein inside neurons that takes on the wrong shape and moves from cell to cell like a rumor in a small town. There is the story of microglia, the brain’s immune sentinels, who become angry and never fully calm down, who try to help and end up setting the village on fire. There is the story of insulin resistance inside the brain, of neurons that starve in a sea of plenty. None of these stories is wrong. They are different windows on the same house. The house is the failure of a system to keep itself clean, fed, quiet, stable, and connected. The house is the slow collapse of clearance, repair, and rhythm in a brain that was built for a different world, a brain that once had the raw materials and the pauses to do its work without interruption (Heneka et al., 2015; Jack et al., 2018).

I began to trace not only what happens inside the brain but also what happens around it. I looked at water, light, micronutrients, movement, social rhythms, and information. I looked at what our species had for the last twenty thousand years and what we have now. I looked at what we removed for the sake of safety and convenience and what that removal cost. Homo sapiens did not evolve in sterilized rooms, under artificial light, with phones that wake the limbic system every ten minutes. This species grew under the sun, in the presence of real darkness, with mineral rich water, with food that carried signals the nervous system understood, and with silence that allowed networks to consolidate, prune, and strengthen. Our biology is tuned to that score. When we change the music, the dance begins to fail. Alzheimer’s disease has many stories that try to explain it. There is the story of amyloid, a protein that aggregates and settles like silt in rivers of cortex. There is the story of tau, a protein inside neurons that takes on the wrong shape and moves from cell to cell like a rumor in a small town. There is the story of microglia, the brain’s immune sentinels, who become angry and never fully calm down, who try to help and end up setting the village on fire. There is the story of insulin resistance inside the brain, of neurons that starve in a sea of plenty. None of these stories is wrong. They are different windows on the same house. The house is the failure of a system to keep itself clean, fed, quiet, stable, and connected. The house is the slow collapse of clearance, repair, and rhythm in a brain that was built for a different world, a brain that once had the raw materials and the pauses to do its work without interruption (Heneka et al., 2015; Jack et al., 2018).

When I speak about water, some people roll their eyes. They think it is a metaphor. It is not. Water is the oldest part of our internal weather. It carries the ions that set the tone of neurons. It buffers acids, moves heat, and transports the minerals that a living brain needs for the simple act of firing and the complex act of becoming. For most of human history, water was not only clean enough to drink, it was alive with the planet. It moved through stone and picked up calcium, magnesium, silicon, potassium, and trace amounts of lithium. It was a low dose, a daily background of balance. It came with no label, no marketing, no promise. It simply did what water has always done. It linked bodies to earth in the simplest possible way. We still say water is life. We rarely mean it. We treat it like plumbing, not cognition.

When I speak about light, people tell me they take vitamin D. And yes, a daily capsule can raise a number in a lab report. It can help. It is not the same as a body that meets the morning with open skin, sees noon with open eyes, and greets darkness when darkness arrives. The vitamin D story is not just about a molecule called 25-hydroxy. It is about circadian clocks in the suprachiasmatic nucleus that read dawn and dim, signal pineal glands to release melatonin at night, and give the hippocampus a chance to move what it learned by day into the deeper places where memory lives. Sunlight builds vitamin D in skin. Light also tells time in the nervous system. Capsules do not tell time. The data are clear that vitamin D participates in neuroimmune balance, calcium handling, and neuronal growth, yet the broader benefit rests on the entire light-dark cycle that guides sleep quality and memory consolidation, not just on a number on a page (Hollis, 2005; Garcion et al., 2002).

When I speak about fat, I do not mean fashion. I mean the material of thought. The brain is a sea of lipids that include omega 3 molecules the body cannot make from scratch. They have to arrive from somewhere. In older diets they arrived from wild fish, from marrow, from organs. They moved into membranes and made them flexible enough to carry signals well. The modern answer is a soft gel. Sometimes it helps. Sometimes the oil oxidizes before it does any good. Sometimes the dose is too small or the form is not ideal for absorption. What matters most is that the brain sees enough of these molecules to build and repair the hardware of memory. The literature on brain function and omega 3 is strong. The specific question of how much gets across the gut and into the brain depends on form, meal context, and the state of the person taking it. This is not a magic bullet. It is a slow correction of a long deficit in a world that has replaced fishing grounds with parking lots and turned meals into marketing (Bazinet & Layé, 2014).

When I speak about lithium, I do not mean a psychiatric prescription. I mean a trace element that shows up naturally in groundwater and that seems to stabilize mood and reduce violence when it is present in small amounts across populations. I mean a daily background dose that our ancestors likely received without knowing it, simply because they drank from places where stone meets water. The epidemiology is not perfect, but it points in one direction. Regions with slightly higher lithium in water often show lower suicide rates and calmer social statistics. This is not a drug story. It is a geology story. It is a story of how tiny amounts of a simple element can shift the tone of a nervous system over years and decades. It is a story of what we took out of our water when we learned how to clean it too well for our own good, and it lines up with what we know about lithium and neuronal signaling at the level of enzymes that shape plasticity and survival, including the regulation of pathways that intersect with tau and synaptic maintenance in ways that concern every researcher who studies degeneration and resilience (Blüml et al., 2013; Ishii et al., 2015; Chiu & Chuang, 2010).

If you put these stories together, you begin to see a pattern. The human brain is not failing because it is weak. It is failing because the environment it expects is gone. The environment that taught a nervous system how to be human included mineral-rich water, full-spectrum light, whole food that carried real signals, long walks, strong social bonds, and long periods without any noise at all. The environment we live in now is chemically depleted and informationally violent. We drink safe water that is empty. We live under light that tells the wrong time. We eat food that has calories but no history. We sit still. We do not sleep. We try to think in the middle of storms of notifications that move through the brain like electric hail. The result is not only stress. The result is physical damage. The result is a hippocampus that shrinks, a default mode network that goes out of tune, glial cells that smolder, and proteins that misfold and refuse to be cleared at night because night never comes in a room full of screens. The result is a species that forgets in plain sight and calls it normal for an age that is not that old (Lupien et al., 2009; Small et al., 2011; Heneka et al., 2015; Jack et al., 2018).

I do not write this as a sermon. I write it as a map. I have watched a person I love lose her present while she holds her past like a pearl. I have watched people try to fix this with pills alone. I have nothing against medicine. I believe in it. I also believe in context. A pill without a rhythm is a lonely thing. A capsule without a change in light is limited. A supplement without a change in water is only a number. If you want a brain to remember, you must give it the world it remembers. You must restore the conditions under which memory evolved to exist. You must bring back the pauses that let neurons file what happened. You must bring back the ions that let neurons fire in the first place.

There is a sentence people use as a joke. Water is life. I want to strip it of its irony and return it to its place. Water is the way the planet writes into us every day. It is the carrier for calcium and magnesium that helps channels open and close. It is the carrier for silicon that shapes connective tissue. It is the carrier for lithium that subtly steadies mood and signal. It is the substance that gives blood the ability to carry and the brain the ability to cleanse. There is no cognition without chemistry. There is no chemistry without water.

There is another sentence people use with pride. I can handle my phone. The data on attention and overload suggest otherwise. Repeated interruptions degrade working memory. Media multitasking correlates with poorer cognitive control and increased distractibility in laboratory tasks that measure the ability to filter irrelevant stimuli. This is not a moral claim. It is a measurement problem that shows up again and again when we test people who believe they are immune to the friction that constant switching imposes on a mind that evolved to run deep, not wide, that evolved to track a hunt across a day, not a feed across a night. Every alert is a demand note against the prefrontal cortex. Every late light keeps the hippocampus from doing what it needs to do when we sleep. Attention is not free. Memory is not free. We pay in synapses and volume when we treat them as if they were (Lupien et al., 2009; Small et al., 2011).

If this sounds stark, it is because I am done with soft language. I do not want to soothe anyone. I want to make the case that if we want to remember, we must become intentional custodians of the conditions that make remembering possible. We must filter water to remove what harms us, then give that water back its living cargo in forms the body recognizes. We must meet morning light and honor night. We must eat food that teaches the immune system calm and gives the brain the fats and minerals it needs to build thought. We must walk. We must speak to one another in rooms where no devices are listening. We must let silence return so that memory has a place to land.

This is not nostalgia. This is neurobiology. The brain that forgets my name is not weak. It is telling me something. It is telling me that a life stripped of the elements that built it will begin to shed the elements that define it. It will start with the nearest hour and back away from the present until only the oldest rooms are left with their lights still on. I can mourn that. I do. I can also learn from it.

I have spent years now following this thread through research that is careful and sometimes cautious to the point of anxiety, as science should be. The strongest patterns keep pointing in the same direction. Degeneration is not a single cause with a single cure. It is the long sum of small deficits in context. It is what happens when clearance and repair fail to keep up with the microdamage of life. It is what happens when night is short, when stress is never discharged, when inflammation is background noise, when water is sterile, when food is empty, when the world is too loud to hear the instructions that nature still whispers into us through rhythms that are older than language.

I am not asking anyone to go back in time. I am asking people to rebuild what time gave us in the simplest ways we can manage inside the world we have. Because this is not only about my mother. It is about me. It is about you. It is about the part of you that is already tired of holding so much shallow information that none of it has weight anymore. It is about the part of you that still knows what a river sounds like and what sleep feels like when morning arrives without an alarm and without a screen. It is about choosing to give your brain the conditions it evolved to trust. Not perfectly. Not all at once. Enough to matter.

I will show you how. I will show you what kind of human walked the earth twenty thousand years ago and how that human drank, ate, and moved. I will show you what our water once carried and what we can give it back. I will show you what supplements can and cannot do, honestly, with the limitations scientists put in their own papers when the headlines do not. I will show you how light can be a drug and how silence can be a teacher. And I will show you how to protect your attention as if it were your blood, because in a very real way, it is.

This is not a theory written from a distance. This is a map written from the edge of a cliff where a family stands and watches a person step away. It is a map for anyone who wants to stay as long as possible in the place where names still match faces and mornings still make sense.

So we begin with water. We begin with the ground itself. We begin with the oldest medicine. We begin with the truth that the brain is not a metaphor. It is salt and fat and light and memory. It is a living archive that needs conditions, not slogans. It is a structure that remembers the planet. And it is asking us to remember it back.

The Ancestral Equation

To understand why humans forget, we must remember who we are. Not who we think we are in this century, but who we have been for tens of thousands of years. Twenty thousand years ago, the Earth was colder. Much of the northern hemisphere was covered in ice. Yet our species, Homo sapiens, survived and spread across continents. The people of that age were anatomically the same as us. The same eyes, the same cortex, the same potential for music, mathematics, and grief. What differed was the environment that shaped their biology.

They lived in a chemical conversation with the planet. They drank from the raw arteries of the Earth, not from taps. Their water was the product of rain that moved through clouds without heavy metal dust, that touched soil not yet stripped by agriculture, and that filtered through stone rich in calcium, magnesium, and silicon. When it reached their mouths, it carried trace elements like lithium, strontium, and boron that acted like soft stabilizers for the nervous system. Each sip carried the fingerprint of geology.

This water was part of what scientists call the primal hydrological cycle. It evaporated from oceans clean of industrial runoff, condensed in an atmosphere free of carbon residue, fell through the open air, and reentered the ground, where it met microbes and minerals that turned it into living chemistry. This was the original loop of life. It was not simply hydration. It was a continuous transmission of information from planet to person.

The earliest Homo sapiens did not need filters. They needed to find sources. They learned which springs made them strong and which made them sick. They followed the taste of salt, the shimmer of minerals, and the smell of iron in the rocks. Water was never neutral. It was the first medicine, the first teacher. The nervous system itself evolved to depend on the precise balance of ions that this kind of water provided. Calcium regulated synaptic release, magnesium balanced excitation, sodium and potassium established electrical gradients. Without them, the brain could not think.

Modern humans still need those same minerals, yet our environment no longer provides them in natural proportions. Tap water in most industrial regions is a manufactured substance. It is chemically treated to remove pathogens and heavy metals, yet the treatment also removes the microelements that once defined biological balance. Chlorine disinfects, but it also reacts with organic material to create byproducts that can irritate the body. Fluoride may protect teeth, but at higher levels it can interfere with thyroid and calcium metabolism. Trace pharmaceuticals now circulate through municipal systems, residues of antibiotics, hormones, and antidepressants that survive filtration. It is water engineered for safety statistics, not for life chemistry.

Most people sense that something is off. So they buy bottled water, trusting labels that promise purity. Yet bottled water is often no better. Many brands simply fill their bottles from municipal sources, add minerals for taste, and sell the illusion of nature. Others extract from aquifers faster than they can refill, turning the planet’s groundwater into a commodity. The plastic that holds the liquid leaches microcompounds into the contents. Heat accelerates the process. Analytical studies have shown that bottled water can contain thousands of microplastic particles per liter, invisible to the eye but measurable in the lab. We drink not from rivers, but from petroleum shaped into convenience (Mason et al., 2018).

When we drink this, we call it progress. But progress should not mean separation from the environment that built us. The brain that evolved drinking mineral water cannot thrive on distilled substitutes. The neurons still need magnesium to modulate excitatory signals, still need calcium to trigger release, still need lithium in trace quantities to maintain mood stability and promote neurogenesis (Chiu & Chuang, 2010). When those elements are absent or low, the system becomes fragile. It is a small imbalance repeated every day until memory begins to fade and stress becomes baseline.

Ancient humans also lived inside light, sound, and silence that carried information. Their days followed the solar rhythm. The endocrine system danced with dawn and dusk. Cortisol rose with the light, melatonin with the dark. Circadian genes expressed themselves in clear cycles. In that rhythm, the hippocampus rested and reorganized every night. In that rhythm, the immune system shut down inflammation and cleared debris. Light and darkness were medicine.

Now the cycle is broken. Artificial light extends the day, screens flood the eyes with wavelengths that confuse the suprachiasmatic nucleus, the small cluster of cells in the hypothalamus that keeps time for the body. When that internal clock falters, every system stumbles. Sleep becomes shallow. Glymphatic clearance, the process that removes metabolic waste from the brain during deep sleep, slows. Beta amyloid and tau accumulate faster when sleep is short or fragmented (Xie et al., 2013). The link between disrupted circadian rhythm and neurodegeneration is not theory; it is repeatedly demonstrated across animal and human studies. The cost of constant light is early decline.

Our ancestors did not know these words. They simply followed the sun. They did not call it sleep hygiene. They called it a night. They also moved constantly. A human who walks ten kilometers a day does not need a gym. That movement was not sport; it was survival. It circulated blood, increased brain derived neurotrophic factor, supported insulin sensitivity, and modulated mood. When muscles work, they release myokines that talk to the brain, signals that promote growth and repair. Modern life replaced that communication with chairs. We sit for hours and wonder why inflammation rises.

The early Homo sapiens diet was another kind of communication. It came from real ecosystems. Wild plants contained more fiber and phytonutrients than modern crops. Meat carried the mineral content of the soil animals grazed on. Fish delivered omega-3 in a form the brain could use. They did not take supplements. They did not need them.

Today we face the opposite extreme. Omega-3 intake has dropped sharply. Grain-fed animals produce less. Farmed fish contain more omega-3 and less DHA. Many people try to compensate with capsules. Yet absorption is complicated. When an omega-3 capsule enters the stomach, gastric acid and enzymes break the oil into free fatty acids and monoglycerides. These then form micelles with bile salts before they can cross the intestinal wall. Bioavailability depends on whether the capsule was taken with food, on the person’s fat metabolism, and on the oxidation state of the oil. A meta-analysis in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition found that absorption rates vary from 20 to 70 percent depending on formulation and context (Bourre, 2006). Much of what people swallow never reaches the brain.

That reality does not mean supplements are useless. It means they are symbolic of something deeper. We are trying to replace an environment with a capsule. We are trying to mimic nature with machines. It is not failure. It is a misunderstanding.

The truth is that memory itself evolved as a survival tool in landscapes that demanded engagement. When you must find your way back to water every day, you remember. When you must recall which berries feed and which kill, you remember. Memory was a navigation device. Today memory is treated like storage space. We fill it with irrelevant data and wonder why the important things disappear. The hippocampus is not a warehouse. It is a sculptor. It shapes and prunes experience. When we overload it, the shape blurs.

Every culture that lived close to the land knew this in practice if not in words. Indigenous peoples around the world ritualized the act of drinking water. They blessed springs. They spoke to rivers. They recognized that their minds depended on the purity of what they drank. This was not superstition. It was empirical observation carried through generations.

We, the descendants of that same lineage, have replaced reverence with chemistry. We use the language of efficiency, not belonging. We treat water as a resource, not a relationship. The brain knows the difference even if we do not.

When we drink remineralized water made consciously, when we step into morning light without glass between us, and when we eat food that still remembers soil, the nervous system responds. Cortisol lowers. Sleep deepens. Inflammation recedes. Synaptic plasticity improves. The data are there. It is not nostalgia. It is measurable physiology (Garcion et al., 2002; Hollis, 2005; Chiu & Chuang, 2010).

To rebuild what we have lost, we must begin with awareness. Every sip, every breath, every beam of light that touches skin is communication. The body is fluent in this language. The question is whether we are still listening.

When my mother drinks water, she often stares at it for a moment. She does not remember the date, but she remembers the ritual. The sound of it pouring into a glass makes her smile. It is small, but it is still connection. It is the most human thing we can do. To drink and to remember what water once meant. That is the ancestral equation. The relationship between environment and mind, between chemistry and consciousness. Forgetting begins when that relationship breaks. Remembering begins when we rebuild it.

The Forgotten Molecules

When I began to trace the chemistry of memory, food kept returning as the quiet evidence. Bones remember diet. Collagen carries the isotopic fingerprints of what people ate. Teeth hold elemental echoes of soil and sea. The microscopic layers in ancient enamel still contain the story of a person’s geography. When I compared those traces from skeletons ten or twenty thousand years old to the laboratory data of living people today, I saw a clear message. We eat more, yet we nourish less.

Early humans lived within an edible ecosystem that spoke directly to biology. Everything they consumed had formed under the same light and within the same mineral loops that shaped their bodies. Wild plants drew micronutrients straight from ground untouched by fertilizer. Animals ate those plants and passed the chemistry upward through the food web. The result was food dense in trace elements and fatty acids that built resilient tissue. That system collapsed when agriculture industrialized. Crops grew faster but absorbed fewer minerals. Soil lost organic matter that once held zinc, selenium, and magnesium. Studies comparing modern vegetables to their mid twentieth century equivalents show declines of up to forty percent in mineral concentration (Davis, Epp, & Riordan, 2004).

The brain depends on a narrow range of nutrients to maintain its structure. Among them are omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin D3, magnesium, zinc, B vitamins, and small amounts of lithium. Each plays a role in the orchestra of memory. DHA, the main long-chain omega-3 in neuronal membranes, modulates synaptic transmission and reduces inflammation (Bazinet & Layé, 2014). Vitamin D3 influences gene expression for neurotrophins that support cell survival (Garcion et al., 2002). Magnesium regulates NMDA receptor activity, the gate through which learning passes. Lithium at trace levels supports enzymes that control plasticity and mitochondrial function (Chiu & Chuang, 2010). When any of these fall low, the system loses harmony.

In the ancient diet, these molecules arrived naturally. Fatty fish in cold rivers carried DHA and EPA. Liver and marrow delivered vitamin D and A in balanced proportion. Seeds and wild greens supplied magnesium and plant omega-3 that the body could partly convert. People ate organ meat that modern palates now reject, yet those organs contained coenzymes and minerals no capsule can reproduce.

Modern humans try to patch the gap with supplements. Shelves overflow with bottles that promise focus, clarity, and longevity. I do not dismiss them. Some help. Yet the biology of absorption is complex. When a person swallows a capsule, the journey from mouth to brain is long. It begins in the stomach, where acid breaks down the coating and frees active ingredients. It continues in the small intestine, where bile salts and transporters decide how much enters the bloodstream. Then the liver filters, modifies, and often discards what remains. Finally, the blood brain barrier, a wall of endothelial cells sealed by tight junctions, lets through only selected molecules. The loss at each stage can be severe.

For omega-3 oils, the average absorption ranges between twenty and seventy percent, depending on form and whether they are consumed with a meal containing fat (Bourre, 2006). Ethyl ester forms common in cheap capsules require pancreatic enzymes that many adults produce inefficiently. Triglyceride forms absorb better but oxidize faster. Even when DHA reaches the blood, only a small fraction crosses into the brain. The rest feeds peripheral tissues or is metabolized. Controlled studies using labeled fatty acids show that plasma increases quickly after supplementation, but cortical incorporation takes weeks and depends on concurrent metabolic health (Bazinet & Layé, 2014).

Vitamin D3 follows another route. Synthesized in skin under ultraviolet B light, it becomes active through two hydroxylations, first in the liver and then in the kidney. Oral supplements can raise serum levels, but they bypass the photochemical signaling that accompanies natural synthesis. The body reads sunlight as both nutrient and timekeeper. Capsules deliver the molecule without the clock. Research confirms that vitamin D receptors in brain tissue respond not only to concentration but also to rhythmic exposure that matches circadian patterns (Hollis, 2005). Artificial intake cannot fully replace solar entrainment.

Magnesium presents its own paradox. It is abundant in nature yet poorly retained in industrial diets. Processed foods lose it during refining. Water treatment removes it. Deficiency affects neuronal excitability and sleep quality. Supplemental magnesium can help, but not all forms are equal. Oxide and sulfate forms pass through largely unabsorbed. Citrate and glycinate forms enter cells more efficiently, but the difference between a body that receives magnesium daily through water and food and one that receives it occasionally through pills is like the difference between rain and irrigation. Continuous flow matters.

Even when supplementation works chemically, it rarely rebuilds the cultural habits that once reinforced those molecules naturally. Our ancestors obtained magnesium by eating plants grown in mineral-rich soil and by drinking groundwater that had touched rock for centuries. They obtained omega-3 by eating whole fish with skin and organs intact, not fillets packed in oil. They obtained vitamin D by living outdoors. Every nutrient arrived wrapped in context. Context shaped absorption as much as chemistry.

The absence of context is what makes modern nutrition fragile. We eat under artificial light, at irregular hours, often alone, while reading news that activates stress pathways. Cortisol interferes with digestion and absorption. Chronic stress also alters gut microbiota, reducing short chain fatty acid production that helps the colon absorb minerals. The gut brain axis is not a metaphor. It is a set of nerve, immune, and endocrine links that respond to both food and emotion. When we eat quickly, we interrupt that communication.

I often think of the gut as the first classroom of memory. Enteric neurons outnumber spinal neurons. They produce ninety percent of the body’s serotonin. They inform the brain about safety and satisfaction. When that system is inflamed or malnourished, cognition suffers. Studies have shown that probiotic interventions can modulate mood and even reduce anxiety scores, evidence that microbial balance and mental balance are entwined (Sampson & Mazmanian, 2015). Our ancestors never took probiotics. They ate living food. Fermented vegetables, aged meat, and raw milk carried microbial communities that trained immunity and shaped neurotransmitter synthesis. We replaced that biodiversity with sterile packaging.

People often ask why they feel tired despite eating well and taking supplements. The answer lies in the quality of energy transfer inside cells. Mitochondria require micronutrients as cofactors. Without magnesium, manganese, iron, and copper, the enzymes of the Krebs cycle slow down. Without CoQ10 and omega-3, mitochondrial membranes lose fluidity. The result is lower ATP production. The brain, which consumes twenty percent of the body’s energy at rest, feels that deficit first. Fatigue of thought is biochemical before it becomes psychological.

Ancient diets rarely produced this state because scarcity imposed fasting and variation that supported mitochondrial renewal. Periodic hunger activated autophagy, the cellular cleanup process that removes damaged components. In modern abundance, constant intake suppresses that rhythm. The body no longer receives the signal to repair. Small inefficiencies accumulate until disease appears. This is not philosophy. It is observation supported by molecular data showing that intermittent fasting enhances neuronal stress resistance and neurotrophic signaling (Mattson, 2012).

The same principle applies to water. Filtered water is often stripped of minerals. Reverse osmosis removes nearly everything. People then add a pinch of salt or a few drops of trace mineral solution to restore balance. It helps, but it remains a reconstruction. Natural water contains ratios refined by geology, not by recipe. Magnesium to calcium, sodium to potassium, and silica content vary with rock type. Those ratios influence taste and physiology. A study comparing different natural springs found measurable effects on hydration and mood linked to mineral composition, particularly the presence of lithium in microgram quantities (Blüml et al., 2013). That small presence may act as a long term stabilizer of signaling pathways that prevent neural overexcitation. Our ancestors drank such water daily.

To many, this may sound nostalgic. It is not nostalgia. It is data wrapped in history. The nervous system that evolved in that environment still expects it. The deficit manifests slowly as irritability, insomnia, forgetfulness, and the creeping loss of cognitive resilience. Modern life tries to solve these symptoms separately: a pill for sleep, a pill for mood, a pill for memory. Each pill ignores the shared cause.

When I walk into a supermarket, I sometimes feel like I am in a museum of substitution. Shelves filled with synthetic versions of what nature once gave freely. Vitamin C pressed into tablets because fruit lost potency during storage. Calcium powders because milk no longer contains what pasture once provided. Omega-3 capsules because fish are rare. Every bottle is a small confession that we have broken the chain.

The solution is not to reject technology but to use it consciously. Supplementation can restore missing links if guided by understanding. But it must go hand in hand with rebuilding the environmental conditions that make those molecules meaningful. If we keep swallowing nutrients while ignoring the light we live under, the water we drink, the movement we avoid, the silence we fear, we will continue to forget.

In the laboratory, when we examine synapses under electron microscopes, we see that memory formation depends on both physical growth and biochemical readiness. New synapses require proteins, lipids, and minerals. They also require time without interference. During deep sleep, the brain replays patterns and consolidates them into stable circuits. That process depends on energy and on the absence of stress hormones. Without magnesium and omega-3, receptor function becomes noisy. Without vitamin D, calcium balance falters. Without lithium, intracellular signaling drifts. In combination, these deficiencies create the background on which age related decline unfolds (Heneka et al., 2015; Jack et al., 2018).

When my mother forgets the present but remembers the distant past, I see that background. It is the slow echo of an environment changing faster than biology can adapt. She grew up drinking water from wells lined with stone eating food grown in local soil. Then the world shifted. Food traveled thousands of kilometers. Water came from pipes. Light extended every night. Her brain carries both eras, and one is fading.

We cannot return to that earlier world, but we can restore its principles. We can eat closer to source. We can choose water that contains minerals rather than slogans. We can respect the rhythm of hunger and rest. We can study the numbers and still listen to instinct. Science is not a replacement for intuition. It is a translation of it.

When I speak about these things in lectures, I see people nodding and then glancing at their phones. I understand. The modern brain is trained to drift. Yet the act of paying attention is itself therapeutic. It increases coherence between cortical networks. It teaches neurons to hold a pattern longer. Attention is nutrition in electrical form.

If we wish to protect memory, we must feed both chemistry and consciousness. The forgotten molecules are not only DHA, magnesium, and vitamin D. They are silence, sunlight, and connection. They are the unseen nutrients of culture. The science supports this more than most realize. Social isolation correlates with higher inflammatory markers and faster cognitive decline. Conversation and shared meals improve glucose regulation and mood (Cacioppo & Cacioppo, 2014). The chemistry of community is measurable.

When I watch my mother talk to an old friend, her eyes light up. For a few minutes, words flow freely. Then the present dissolves again. But in those moments, I see what the brain can still do when given the right signal. It remembers relationships even when it forgets chronology. That is the proof that memory is more than storage. It is participation.

The lesson of the forgotten molecules is that biology is cooperative. Every system depends on another. When we isolate nutrients, we lose the network. The task is not to collect more bottles but to rebuild that network in daily life. Eat real food. Move often. Sleep deeply. Drink living water. Seek sunlight. Speak kindly. None of this is alternative medicine. It is original medicine.

The future of cognitive health will not be found only in laboratories. It will also be found in how we return complexity to our environment. Complexity is not chaos. It is richness. It is the mineral signature of life itself. The more diverse our inputs, the stronger our resilience. This is the same law that governed the forests our ancestors walked through and the microbiomes inside their guts. Diversity equals stability.

In the end, forgetting begins when diversity dies. Remembering begins when it returns.

The Brain in Noise

There is a sound that few people notice anymore. It is the sound of silence that used to fill the spaces between thoughts. For thousands of years, that silence was the background on which memory wrote its stories. The brain evolved in that quiet. It learned to observe, to predict, to imagine. The early Homo sapiens mind had time to wander and to rest. Every sound in the natural world carried meaning. Wind in the grass meant movement. A bird’s call meant season. A river’s rhythm meant water. Noise was information, not interference.

Today the situation is reversed. Noise no longer signals meaning. It fills every gap. It has become the constant condition of modern life. Phones vibrate, screens flash, engines hum, notifications multiply. The nervous system never completes a cycle of rest. Even when the room is still, electromagnetic and visual noise persist. We live inside a storm of small demands.

When I began to study this more closely, I saw that what we call distraction is not only psychological. It is biochemical. Each interruption activates the stress response. The hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis, the chain of communication that connects the brain to the adrenal glands, releases cortisol and catecholamines. These hormones were designed for danger, not for data. They increase heart rate, mobilize glucose, and sharpen attention for a few minutes. Then they are supposed to fall. In a natural environment, they did. After the danger passed, the body returned to baseline.

In the digital environment, there is no baseline. The stimulus never stops. Every message, every headline, every new sound restarts the cascade. The brain does not distinguish between a threat and a notification. Both demand a response. Over time, cortisol remains elevated. Chronic exposure to high cortisol shrinks dendritic branches in the hippocampus, the region most responsible for forming new memories (Lupien et al., 2009). The result is impaired learning and accelerated aging.

The same stress hormones that help us survive emergencies become toxic when they never leave the bloodstream. They damage sleep, they alter immunity, and they promote inflammation that feeds back into the brain through the vagus nerve. The link between chronic stress, inflammation, and neurodegeneration is among the most consistent findings in neuroscience (Heneka et al., 2015). Microglial cells, the brain’s immune guardians, switch from maintenance to alarm mode and begin to secrete cytokines. In small amounts, these chemicals protect. In excess, they erode synaptic connections.

The average person today checks their phone hundreds of times a day. Each check is a micro stressor. Each one activates a small burst of dopamine that anticipates reward. When the reward is inconsistent, as it usually is, dopamine pathways become dysregulated. This is the same principle that governs addiction. The nucleus accumbens and ventral tegmental area, parts of the brain’s reward system, adapt to the cycle of anticipation and disappointment. They crave more stimulation to reach the same feeling of satisfaction (Small et al., 2011). The result is a restless mind that seeks novelty at the expense of depth.

When people tell me they cannot focus, I remind them that focus is not a talent. It is a condition. The brain cannot hold attention in an environment that constantly demands redirection. Attention requires safety, time, and meaning. Without them, neural coherence disintegrates. Electroencephalography studies show that multitasking increases beta wave activity associated with stress while reducing the alpha rhythms associated with calm focus. It also lowers working memory performance by measurable margins (Ophir, Nass, & Wagner, 2009).

The digital world rewards the opposite of what memory needs. It rewards speed, not reflection. It rewards reaction, not retention. Every scroll resets context. The hippocampus struggles to integrate information when context changes faster than it can consolidate. That is why many people today remember fragments but not sequences, impressions but not stories. Memory thrives on continuity. Our ancestors told stories around fire because story was the structure of thought. The modern feed destroys story.

When we measure brain activity during rest, we see a network called the default mode. It is active when the mind is not focused on an external task. It connects regions involved in self reflection, memory, and imagination. This network integrates experience into identity. In silence, it hums. Under constant input, it fragments. Chronic noise suppresses the default mode network and replaces introspection with reaction. People begin to live in a perpetual present that never becomes past because nothing is allowed to settle (Raichle, 2015).

Sleep should restore this balance. During deep slow wave stages, the brain replays patterns and clears waste through the glymphatic system, a series of perivascular channels that flush out metabolic debris (Xie et al., 2013). Yet noise, both auditory and informational, interferes with this. The glow of screens delays melatonin release. Late-night messages keep the limbic system alert. Even if the person sleeps, the quality of that sleep is shallow. Without slow wave phases, consolidation fails. What was learned by day is not filed away by night. The next day begins already tired.

Silence is not a luxury. It is maintenance. The absence of silence is a pathology. I have measured its effects in people who live near highways compared to those who live in rural areas. Their cortisol profiles differ. Their blood pressure differs. Their sleep differs. The body hears even when the mind pretends not to.

There is also social noise. The constant exchange of opinions, outrage, and fear on networks acts as a form of emotional pollution. The amygdala, which evolved to detect danger in immediate surroundings, cannot distinguish between a physical threat and a digital one. Each alarming post triggers the same pathways. Chronic activation of the amygdala reduces its connectivity with the prefrontal cortex, impairing regulation of emotion. The result is anxiety, irritability, and impulsive judgment (Pessoa, 2017).

When I step away from the city into mountains or forest, I can feel the nervous system recalibrate. It is not imagination. Heart rate variability increases. Breathing deepens. The parasympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system reasserts control. Studies show that even brief exposure to natural environments lowers salivary cortisol and enhances mood (Ulrich et al., 1991). This is the physiological signature of peace. The body knows what the mind forgets.

I sometimes think of attention as the new metabolism. Just as the body once burned physical fuel to move, the mind now burns informational fuel to think. When the intake is chaotic, the metabolism becomes inefficient. We waste cognitive energy on irrelevant stimuli. We live in constant partial awareness. The hippocampus receives too much data and too little meaning. It cannot prioritize. Over time, that noise translates into neural fatigue.

It is not coincidence that anxiety, depression, and cognitive decline are rising together. They share mechanisms. All involve chronic stress, inflammation, and disrupted signaling. The modern information diet resembles the modern food diet: abundant, addictive, nutrient poor. We consume, but we do not assimilate.

When I visit my mother, I often sit beside her without talking. She looks out the window and follows the movement of trees. She does not check messages. She does not remember the date. But her breathing slows. Her hands relax. In that silence, I see something the rest of the world has forgotten. Awareness without demand. That is what the brain needs to heal.

Restoring that state is not complicated, but it requires choice. Turn off devices two hours before sleep. Go outside at dawn. Read a single page without music. These are not trivial acts. They are acts of repair. Each one lowers cortisol and raises coherence between networks. Each one teaches the nervous system that the storm is over.

The first step is to recognize that attention is finite. Neuroscientists have measured the refractory period that follows each shift in focus. It takes several minutes for the brain to return to full capacity after an interruption. Multiply that by hundreds of interruptions per day, and we begin to see why we feel exhausted. The cure is not more productivity. The cure is fewer interruptions.

The noise we live in also distorts identity. The self becomes a performance for invisible audiences. Validation replaces meaning. Dopamine drives behavior in loops that never satisfy. In anthropology, identity once came from function and relationship. In the digital age, it comes from reflection in screens. This weakens the roots of memory because memory is anchored in genuine experience. Without grounding, the mind drifts.

To recover identity, we must return to direct contact with life. Touch real objects. Taste real food. Hear natural sound. The brain records these with richer detail than digital ones because they engage multiple sensory channels. A message on a screen stimulates sight and thought. A river engages sight, sound, smell, and motion. Multisensory experiences form stronger memories (Small et al., 2011). This is why people remember their childhood summers by smell and sound more than by words.

The constant presence of devices also changes posture and breathing. The forward bent position compresses the chest and reduces oxygen intake. The brain receives less oxygenated blood, especially in the prefrontal cortex. Mild hypoxia impairs decision-making. Extended screen time also reduces blinking, leading to eye strain and sympathetic activation. These small physical stresses add up to large cognitive costs.

There is a growing field called digital hygiene, which studies how to design healthier relationships with technology. Its recommendations often sound simple: schedule screen-free periods, disable unnecessary alerts, use grayscale modes to reduce stimulation. Yet behind these simple steps is profound neurobiology. The brain that receives fewer random signals reestablishes its natural rhythm of anticipation and reward. Dopamine levels stabilize. The limbic system relaxes.

None of this is about rejecting modernity. It is about reintroducing proportion. The human nervous system can adapt to many environments, but adaptation has limits. The speed of information growth has surpassed the speed of biological change. We cannot expect a brain designed for direct experience to process constant abstraction without cost.

Silence, rest, and presence are not luxuries. They are prerequisites for the maintenance of memory and self. They are the natural states in which neurons reconnect and reorganize. They are also the spaces where insight arises. Creativity emerges from silence, not from noise. Every time I switch off my phone and walk outside, I am not disconnecting. I am reconnecting to the original network that made consciousness possible. Trees, wind, water, and light speak in frequencies older than language. They speak directly to the nervous system. They lower heart rate and restore coherence between mind and body. They make remembering possible again.

Our ancestors did not meditate to calm themselves. They lived in an environment that provided calm. We must now recreate it intentionally. That is the task of this century: to build spaces where the brain can rest, to design rhythms that honor our biology, and to remember what silence sounds like.

Because forgetting begins with noise, and remembering begins with quiet.

Back to the Roots

When I began to connect the patterns, it felt less like discovering something new and more like remembering something old. Every cell in the body seems to carry the memory of an older world. It is as if the genome itself remembers sunlight, clean water, movement, and silence. We call these things lifestyle, but they are not choices. They are the environmental conditions that shaped the species.

To go back to the roots does not mean walking backward through time. It means restoring the conversation between body and planet that has been interrupted. The modern world is not evil. It is incomplete. We have built comfort at the cost of context. The task is not to abandon progress but to integrate it with memory.

When I look at the data that describe longevity and health across cultures, one truth repeats itself. People who live the longest are not necessarily those with the best medicine. They are those whose daily lives still include traces of the ancestral environment. They walk. They work outdoors. They eat fresh food. They maintain social bonds. They experience darkness at night and light at day. Their water carries minerals. Their meals carry meaning.

In Okinawa, Sardinia, and parts of Costa Rica, communities often called blue zones share these traits. Their diets vary, but the underlying pattern is balance. They eat vegetables grown in local soil, fish from local waters, and small portions of meat. They do not count calories. They live by rhythm. Their microbiomes mirror their environment. Their inflammation markers are low. Their incidence of Alzheimer’s disease and depression is lower than that of industrial populations (Buettner, 2012). These are not isolated miracles. They are evidence of what happens when human biology and environment stay aligned.

Contrast that with the modern average. The typical day for many involves waking to an alarm, drinking processed coffee with purified water, eating refined carbohydrates under artificial light, and sitting for hours. Movement becomes exercise instead of necessity. Food becomes content instead of communion. Water becomes a product instead of participation. The result is biochemical confusion.

When we speak of prevention, we often focus on genes. Yet genes express themselves through environment. The science of epigenetics shows that DNA is not destiny. Methylation patterns, histone modifications, and microRNA interactions respond to lifestyle. Chronic stress changes them. Diet changes them. Light changes them. Even thought changes them. These mechanisms do not alter the sequence of genes; they alter which genes are read. The modern environment reads the genome in a language it never learned to understand. That mismatch may explain much of what we call aging.

Alzheimer’s disease can be viewed through this lens. The pathology may begin decades before symptoms appear. It develops in the context of inflammation, insulin resistance, and oxidative stress. Each of these factors is influenced by environment. Diets low in omega-3 and high in sugar increase inflammation. Sedentary behavior reduces insulin sensitivity. Chronic stress increases oxidative load. Together they create a field in which amyloid and tau pathology can flourish (Heneka et al., 2015). The disease is not inevitable. It is ecological.

Going back to the roots means rebuilding that ecology. It begins with water. Real water. Not distilled or chlorinated or stored for months in plastic. Water that contains the mineral balance nature intended. Calcium, magnesium, and trace lithium help maintain stable neuronal signaling. Studies show that even microgram levels of lithium in drinking water correlate with lower rates of cognitive decline and suicide (Blüml et al., 2013). It is not medication. It is the planet whispering chemistry into blood.

It continues with light. Humans need sunlight not only for vitamin D but for timekeeping. The body runs on circadian rhythms that coordinate thousands of genes. Morning light triggers cortisol peaks that prepare the brain for focus. Evening darkness triggers melatonin release that prepares the brain for repair. Disrupting these rhythms confuses the endocrine system and weakens immunity. A simple act of stepping outside at dawn and avoiding bright screens at night can recalibrate hormones and improve sleep within days (Garcion et al., 2002).

Next comes food. The brain is made mostly of fat and water. Every synapse depends on membranes built from omega-3. The modern diet tilts heavily toward omega-6, found in vegetable oils. That imbalance fuels inflammation. Reversing it requires conscious choice. Wild fish, grass fed meat, flaxseed, and algae contain the forms the body needs. Supplementation can help, but absorption improves when taken with real meals. The goal is not to chase numbers but to restore ratios.

Magnesium, zinc, and selenium are equally vital. They support hundreds of enzymes involved in energy and antioxidant defense. Their deficiency is widespread because industrial agriculture strips soil of these minerals. Remineralized water, nuts, seeds, and greens can help rebuild reserves. Research shows that higher magnesium intake is associated with lower risk of dementia and improved cognitive performance (Loera-Castañeda et al., 2022).

Another forgotten nutrient is connection. Loneliness activates the same brain regions that respond to physical pain. Social isolation increases inflammatory markers such as interleukin 6 and C reactive protein. Chronic inflammation erodes synaptic function. Community, conversation, and touch act as biological buffers. People who engage socially show slower cognitive decline even when pathology exists (Cacioppo & Cacioppo, 2014). Connection is medicine.

Movement is another form of nutrition. Every contraction releases myokines that communicate with the brain. They promote neurogenesis and modulate mood. Regular physical activity increases hippocampal volume and memory performance (Erickson et al., 2011). The form of movement matters less than its presence. Walking, gardening, dancing, cleaning, carrying wood… all count. Our ancestors moved to live. We must live to move.

And then there is rest. True rest. Sleep is not optional. It is the nightly reorganization of experience. During deep sleep, neurons reduce activity, glial cells open pathways, and cerebrospinal fluid flows to remove waste. Amyloid clearance increases during these hours (Xie et al., 2013). When sleep is short, toxins accumulate. The modern habit of sleeping less than seven hours correlates with higher risk of cognitive impairment. The solution is simple and radical: protect sleep as sacred.

There is a psychological root to all of this. The human mind evolved to handle complexity but not chaos. It needs purpose. It needs rhythm. The digital economy trains us to react, not to create. Going back to the roots means reclaiming agency over attention. The act of focusing on one thing fully, even for minutes, trains neural circuits of stability. Meditation, slow breathing, or simply watching water move can reset the nervous system. These are not spiritual clichés. They are neurobiological interventions supported by imaging studies that show increased prefrontal activation and decreased amygdala reactivity after consistent practice (Tang, Hölzel, & Posner, 2015).

When I tell people to return to nature, they often imagine a retreat or an escape. I mean something smaller and closer. Open a window. Walk outside without headphones. Eat without a screen. Speak to someone face-to-face. These are the acts that rebuild the dialogue between humans and the world.

We are designed for such simplicity. The nervous system still measures the world through the same senses it always had. Taste, smell, touch, sound, and sight are not optional pleasures. They are the inputs through which the brain calibrates its chemistry. Artificial environments provide distorted signals. Plastic surfaces, synthetic fragrances, and digital light confuse the system. Returning to natural textures and sounds restores coherence.

In anthropology, health was never an individual property. It was a state of harmony between person, community, and environment. Modern medicine separates these, but the separation is recent. Indigenous healing practices around the world still operate on the principle of balance rather than battle. They do not fight disease; they reestablish flow. Science is beginning to rediscover this truth in the language of systems biology. The body is a network, not a machine.

Going back to the roots also means confronting belief. Many people wait for permission from authorities to do what common sense already tells them. They fear simplicity because it sounds unscientific. Yet science itself began as observation. When we observe carefully, we see that health follows the same patterns everywhere: clean water, real food, light, movement, sleep, connection, purpose. Each supports the others. Remove one, and the rest begin to wobble.

In my own life, I learned this through contrast. The years I spent in laboratories and courts were full of noise, deadlines, and fluorescent light. My mind was sharp but brittle. When I began to spend more time outdoors, to drink water that came from the ground, to move daily without devices, something changed. Clarity returned. Fatigue faded. Thought became easier, not faster but deeper. I did not discover new truths. I returned to old ones.

When I visit my mother now, I bring her outside whenever I can. We sit in sunlight. She closes her eyes and tilts her head toward warmth. She does not know the year, but she knows the feeling. Her breathing slows. Her body remembers what her mind has lost. That is what I mean by roots. Beneath memory lies recognition. The body recognizes truth long after the brain forgets.

Going back to the roots is not regression. It is evolution remembering its path. The goal is not to imitate the past but to understand what made it stable. The first step is awareness. The second is practice. The third is patience. The process is slow because biology is slow. But every small correction accumulates. A few weeks of better light improves sleep. A few months of mineral rich water stabilizes mood. A year of movement changes brain structure. Time is the medium of recovery.

In the end, we do not need to invent a new kind of human. We need to remember how to be the kind we already are. The genome that built cave paintings also built computers. It can handle both if given the right foundation. What it cannot handle is disconnection from that foundation. The cost of forgetting the roots is forgetting ourselves.

The future of neuroscience will not only be in microscopes but in mirrors. We will look at our own lives as experiments in environment. We will measure the chemistry of belonging. We will see that the most advanced medicine is sometimes the simplest.

Because in the silence between thoughts, under the skin, and within the pulse, the old dialogue still waits. It says, drink real water. Eat real food. Rest when it is dark. Move when it is light. Speak to one another. Remember what you are made of.

That is what it means to go back to the roots.

Memory as a Mirror

Every science eventually becomes philosophy when it reaches its limits. The study of memory is no exception. The more I learn about the brain, the more I realize that memory is not only a biological function. It is a reflection of relationship, between the self and the world, between neurons and experience, and between chemistry and meaning. To forget is to lose that relationship. To remember is to rebuild it.

When I look at my mother, I see this truth embodied. Her brain has lost much of its recent structure, yet she is still herself in fragments. She remembers melodies, scents, and textures long after names vanish. She reacts to kindness and to tone. She responds to sunlight. She still laughs at rhythm. These are not coincidences. They are evidence of layers of memory that survive the decay of others. The oldest networks in the brain are sensory and emotional. They live deeper than language. They are shaped by repetition and by love.

Watching her taught me that forgetting is not uniform. It begins at the edges of the present and moves backward, like a tide retreating from shore. What remains longest are those experiences saturated with meaning. The smell of coffee in the morning, the warmth of skin, the sound of a familiar song. These memories are anchored not only in the hippocampus but in distributed networks that involve the amygdala, the insula, and the sensory cortices. They are also reinforced by dopamine and oxytocin, the biochemistry of connection (McGaugh, 2013).

In evolutionary terms, this makes sense. The brain preserves what aids survival. Emotional memories guide behavior. They tell us what to seek and what to avoid. The loss of factual memory in Alzheimer’s disease does not erase this ancient system. It only disconnects it from chronology. My mother still knows kindness when she feels it. She still recognizes rhythm. Her memory has become a mirror of emotion, stripped of time.

From a scientific point of view, memory is the constant rewriting of synaptic connections. Each time we recall, we edit. Each act of remembering is an act of creation. This process is called reconsolidation. It explains why memory can change yet remain believable. It also means that identity is not static. It is maintained through continual rehearsal. In a world where attention is fragmented, that rehearsal weakens. We no longer give ourselves time to revisit meaning. We accumulate information without integrating it. The result is a shallow archive that feels full but is easily lost.

Memory needs silence as much as it needs stimulus. During quiet, the brain replays patterns, sorts relevance, and strengthens connections. This replay has been recorded in animal models where neurons in the hippocampus fire in the same sequence during rest that they used during exploration, compressing hours into seconds. This is how experiences become memory (Wilson & McNaughton, 1994). In humans, functional imaging shows that offline activity in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex predicts later recall. Without rest, there is no consolidation.

That is why the constant noise of modern life is not just unpleasant. It is amnesia disguised as culture. The flood of information outpaces the capacity to store. The human brain evolved to encode patterns that mattered: faces, landscapes, dangers, and stories. It did not evolve to track endless fragments of news. When it tries, it exhausts itself. The hippocampus begins to shrink under chronic stress (Lupien et al., 2009). The prefrontal cortex, which manages attention, loses efficiency. We mistake this fatigue for boredom or for aging, but it is neither. It is saturation.

There is another layer to memory that science measures less easily: narrative. The sense of continuity, of being the same person across time, depends on the ability to link past to present. When memory fractures, narrative fractures. This is what I see in my mother’s eyes when she looks at me and cannot place me. She remembers herself but not her timeline. She has become a series of moments without thread. It is heartbreaking because it reveals what makes us human. We are not only aware. We are aware of sequence.

Rebuilding narrative is one way to fight forgetfulness. Writing, speaking, sharing stories reactivates networks that bind identity. That is one reason therapy works. It gives the mind space to reconstruct coherence. The brain thrives on pattern. When experience lacks pattern, anxiety rises. When pattern returns, calm follows.

From anthropology, we know that storytelling was once central to every culture. It transmitted history, values, and belonging. It was also exercise for the brain. Reciting stories demanded memory and imagination. Listening demanded attention and empathy. These communal rituals strengthened cognition long before books or screens existed. In modern life, we consume stories passively. We binge them. But we rarely create them. Creation is the act that strengthens memory. Consumption alone weakens it.

Philosophers have long argued that consciousness is a loop of memory looking at itself. The mirror metaphor fits because what we recall shapes what we perceive next. A brain that remembers abundance perceives opportunity. A brain that remembers fear perceives threat. The content of memory becomes the lens of life. When disease erases that lens, perception collapses. But even then, traces remain. The emotional palette persists. That is why music can reach where words fail. It bypasses damaged networks and touches intact ones. Music therapy activates the same dopaminergic pathways that respond to food and love. It revives attention through pleasure. Clinical studies show measurable improvement in mood and orientation in Alzheimer’s patients exposed to familiar melodies (Särkämö et al., 2013).

Memory also depends on metabolism. The brain’s energy demand is high, and neurons rely on glucose and ketone bodies to fuel synaptic activity. When insulin signaling falters, neurons starve. Some researchers call Alzheimer’s disease type 3 diabetes because of this metabolic dysfunction (de la Monte & Wands, 2008). The link between nutrition, metabolism, and memory is strong. Diets that stabilize blood sugar, such as those rich in fiber, unsaturated fats, and moderate protein, support cognition. Intermittent fasting increases ketone production and upregulates brain derived neurotrophic factor, enhancing resilience (Mattson, 2012).

These details might seem technical, but they describe what happens in every moment of forgetting. When my mother hesitates before a word, somewhere a synapse fails to receive enough energy. Somewhere a protein misfolds. Somewhere a glial cell tries to repair damage and cannot. Yet she still smiles. That smile proves that the essence of life is more than the sum of its mechanisms. It reminds me that memory is not limited to neurons. It extends into relationships.

When people speak of immortality, they imagine technology or religion. But there is another form of survival: influence. The gestures we repeat from our parents, the words we borrow, the habits we teach. These are echoes. They are cultural memory. They outlast the individual. My mother may forget my name, but her voice is in my thoughts, her phrases in my speech, her calm in my patience. She continues. Memory migrates.

This realization changes how I see science. The goal is not to conquer aging. It is to understand belonging. The brain forgets when it becomes isolated, from minerals, from light, from silence, from touch, from story. The cure is not only molecular. It is relational.

Back to the roots means not only physical practice but also psychological humility. It means accepting that cognition is ecological. The mind extends into the environment. The neurons of one person link to the neurons of another through language and empathy. Social neuroscience has shown that during conversation, the neural rhythms of two people synchronize. This phenomenon, called interpersonal neural coherence, correlates with understanding (Stephens, Silbert, & Hasson, 2010). In this sense, remembering together is easier than remembering alone.

We can design societies that support this coherence or destroy it. Public noise, stress, inequality, and fear fragment it. Shared meals, art, kindness, and trust restore it. Each act of connection is a small act of preservation. It keeps the human network alive.

The next frontier of neuroscience may not be inside the skull but between them. The collective nervous system we create through culture will decide how much we remember as a species. Forgetting environmental responsibility, forgetting empathy, forgetting patience are all symptoms of the same disorder: disconnection. The same processes that erode personal memory erode collective memory.

This is why returning to silence and simplicity is not retreat. It is resistance. It is the refusal to let noise erase depth. It is the choice to think clearly in an age that profits from confusion. It is the act of building memory where distraction wants amnesia.

When I stand by a spring and watch water flow, I think of neurons firing. Each ripple is an impulse, each stone a cell, each leaf a thought. The water carries memory of its path. It shapes the ground it passes through. The same is true of experience. It changes the structure it travels. Memory is the trace of that change.

If there is one lesson in all of this, it is that remembering is active. It requires participation. It is a discipline of care. Drink real water. See real light. Move the body. Rest the mind. Speak the truth. These are not slogans. They are the protocols of longevity written in biology.

When people ask me what the future holds, I tell them I do not know. But I know what the past demands. It demands awareness. It demands gratitude for the chemistry that keeps thought alive. It demands that we respect the conditions under which consciousness appeared.

In the mirror of memory, we see both what we have been and what we might become. Forgetting is a warning. Remembering is a choice.

I sit in silence and watch the light move across the wall. Dust floats like memory, alive for a moment, then gone. In that shifting glow, everything returns: the lineage of water, light, food, silence, and love that made us human. The mirror clears. For a second, the world remembers itself. I see reality as it is. Everyone should find their own way, talk to their doctor, and think before taking things without reason. Curiosity is good, awareness is better, but wisdom means knowing your limits.